Interstellar Propulsion - Part 1

Date: 03/01/2025

Author: Chris Hajduk

For the past few years I've been thinking alot about the potential for a new method of massless propulsion. Notably, many previous attempts at massless (reactionless) propulsion have been published or considered, but usually they follow fringe-science and claim to exploit physics that are poorly understood. The most famous of which is the EmDrive, but there are countless others that have been proposed but do not have any merit. Nonetheless, there are a two well-established propulsion techniques that are indeed massless: Sails and Photon-based Propulsion.

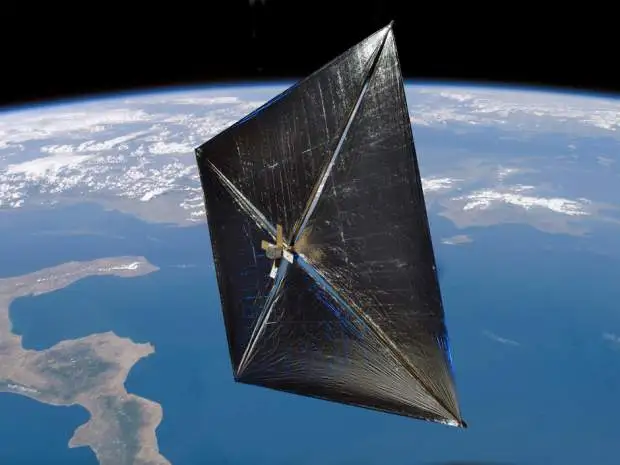

A render of a conventional solar sail.

A render of a conventional solar sail.

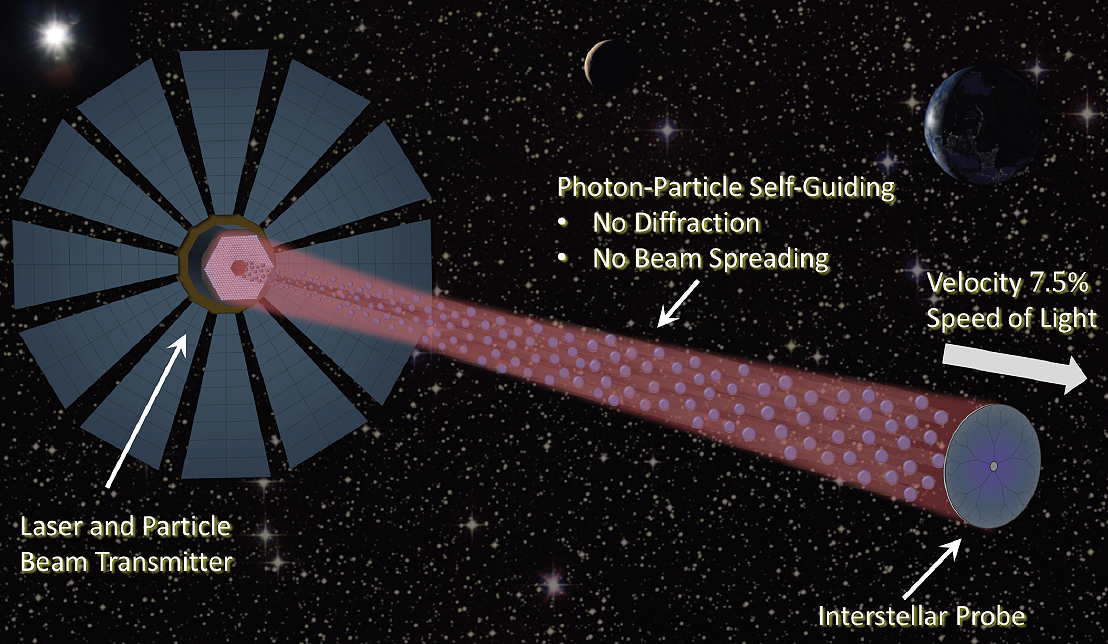

A method of photonic propulsion.

A method of photonic propulsion.

By "Sails", I am referring to all manners of propulsion using the solar output to impart a force on the spacecraft. Solar sails are the most common version. However, magnetic and electric solar sails have also been theorized (but untested). The idea mostly revolves around the fact that sun (or any star) has a certain amount of solar radiation pressure being exherted in all directions. A standard solar sail would create a force from both the solar wind (mostly protons and electrons) as well as the solar radiation (photons) being emitted from the star itself and reflecting off the sail. For a typical solar sail, the radiation pressure amounts to about 1000 times the force of the corresponding solar wind, which goes to show how sparce the solar wind is (. Nonetheless, prototypes of solar sail spacecraft have been built - for instance - the Planetary Society has launched solar sail cubesats into space (see the LightSail program). Large scale demonstrations are untested and there is still further work and research that needs to be done. The largest contributor to the lack of solar sails continues to be a combination of technical and economic feasability. Designing a lightweight, reflective solar sail with an functional deployment mechanism is a large technical challenge - not to mention the need to be able to continuously accurately control the sail position to maintain attitude. The size and complexity of such a system is large for such small net force. Nonetheless - this is propellant free! Nearly all other forms of propulsion require carrying fuel onboard.

A render of a electrostatic sail.

A render of a electrostatic sail.

Typical solar wind measurements.

Typical solar wind measurements.

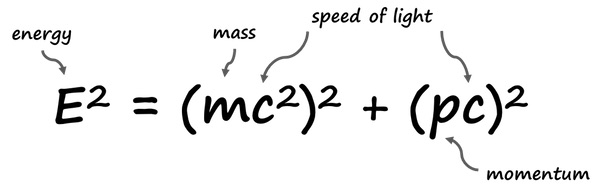

Photon-based propulsion (which has some overlap with solar sails) is another way to propel a spacecraft in space without any onboard reaction mass. Simply pointing a light source (laser) away in the opposite direction of travel will generate some force. Einstein's equation for mass-energy equivalence, E = mc^2, actually is only part of the full equation. The full equation is E^2 = m^2 * c^4 + p^2 * c^2. Without the mass, component we can simply focus on the later part of the equation: E = p * c. Since light carries momentum, this means we can create an equal and opposite force with an appropriate photon of light. A space craft using this force would be called a Photon Rocket. However, upon initial examination one can quickly see the issues with photon propulsion: 1N of force would require approximately 298MW of power to create the necessary photons. That is the equivalent power output of 1/3 of a nuclear fission power plant. That is a crazy amount of power! In space! The process would need to be exteremely efficient too, because any waste heat would be very difficult to handle in space (radiators in the rear of the spacecraft would probably be necessary). I (and probably many others) believe that this is our CURRENT best method to achieve interstellar propulsion. The best solutions right now, propose that the laser source would be stationed on the ground (on Earth or the moon) and the target spacecraft would be tiny and solar-sail-like (See Breakthrough Starshot).

The full version of Einstein's famous Energy-Mass-Momentum equivalence.

The full version of Einstein's famous Energy-Mass-Momentum equivalence.

At the end of 2018, when I first began to think about this issue, I thought - "There has to be a more energy efficient way to propel spacecraft". On one hand, we have solar sails which are perfectly efficient but have limited use cases. On the other hand, a powerful enough photon rocket could be use in any in-space use case, but it is so inefficient it is practically infeasible. My second realization was that literally every reliable method of transportation uses the environment to "push against". Ground vehicles (cars/bikes/trains) use the pavement as a means to generate a forward force. Boats use water. Planes use air. Rockets - well - why don't they use the solar wind? The correct answer is two-fold: Density and speed. First of all, the solar wind is very sparce - there are roughly 5 particles per cubic centimeter. Almost nothing! What is even worse is that the solar wind is travelling at an astonishing rate. While the speed varies depending on the solar weather, particles can reach up to speeds of 400 km/s. Conservation of momentum dictates that in order to impart a momentum on an object - an equivalent and opposing momentum change needs to be imparted elsewhere. That means that you can either act like a sail and transfer the momentum of the solar wind onto the spacecraft by reducing the speed of the solar wind or you can do the opposite and accelerate the solar wind even faster. Being able to do both would provide the flexibility of being to accelerate the spacecraft in any direction. Furthermore, if momentum can be transferred freely between solar wind particles and the spacecraft in large quantities, it may become more feasible than the current photon-based propulsion techniques described above. The key metric is energy-momentum conversion efficiency or force-power efficiency (I will use force-power efficiency). To be more effective than photon-based propulsion, the power efficiency factor needs to be greater than 1N/298MW of power (3.35e-9 N/W). In a future post, I will present some of my original thoughts on this matter and a few posts later I will eventually hypothesize a new/different form of interstellar propulsion that may provide greater efficiency.

Before ending this post, I want to add that two notable concepts have been a significant contributor to this idea (which will be detailed in the next post). The first concept of a Dipole drive was presented by Robert Zubrin at the 2018 Breakthrough Discuss conference. The concept is severely flawed in that it doesn't obey the laws of physics (electric field equations used in his presentation are approximations which present inaccurate conclusions). The second idea was published in a journal, depicting a spacecraft soaring through the wind similar to the way birds do in regular wind here on Earth. Both of these had an impact on my thought process over the last few years, and one may notice some the similarities of these concepts in upcoming posts.